Episode Transcript:

Introduction

[00:00:00] Mokaya: Welcome to The Mwango Capital Podcast. At Mwango Capital, we aggregate key information on African capital markets through Twitter, Telegram, and our weekly newsletter called The Baobab. We also hold weekly discussions every Friday on topical issues on African capital markets, and we also engage in analysis and research, and training. We look forward to another engaging conversation on our Twitter Spaces, so join us there every Friday so that you can keep having quality conversations on African capital markets. Without further ado, welcome to today's conversation.

Welcome to our Twitter Spaces today. Today's conversation is about Centum, and we are privileged to have the CEO here today. Centum is unique in the sense that I don't think it has a peer at the Nairobi Stock Exchange. It would be nice to get a deep dive into this company from the CEO himself. He’s spent quite a chunk of time in this company himself, so he should understand the nooks and crooks of it. So we'll start off by asking that you can introduce yourself to those who don't know you. I'm not so sure there are many, but it would be nice to have a quick thumbnail sketch of who you are and what you do.

[00:01:26] James: Thank you, Erick. This is James Mworia. I'm the Chief Executive Officer of Centum Investment. It's a pleasure to be on this platform today and looking forward to sharing the highlights. As Eric has explained, I have been with the company since 2001, so 20 years, the last 12 of which I have been its CEO.

[00:01:48] Mokaya: It would be interesting also to hear how you got started in your career? Did you know that you wanted to be at Centum from an early age?

[00:01:57] James: No, not really. I studied accounting at Strathmore and Law at the University of Nairobi. When I completed my law studies just before graduation, I secured an internship at Centum. It was then called ICDCI, and I joined to do all manner of work; clerical work, accounting work, investment work, filing work. I started off in the filing room and I enjoyed reading the files. The last equity raise that Centum did was some time in May of 2001 and the then-CEO Tony Wainaina administered a quiz on the staff on their knowledge of the business, and I did well, and that's how I got a job.

I started off on the accounting side, accounting for portfolio companies. I then moved into operations supporting various portfolio companies and eventually in 2005, I then became the Investment Manager. I was Investment Manager for a while, left briefly to join another organization, then I was asked to come back as the CEO in December 2008. It's been an interesting journey. So, I do not know I would end up in investments. I did not know I had an interest in investments, and that's how I found myself in this organization.

I started off on the accounting side, accounting for portfolio companies. I then moved into operations supporting various portfolio companies and eventually in 2005, I then became the Investment Manager.

What Inspires You?

[00:03:22] Mokaya: Maybe following up on that, then I would ask what inspires you day to day and what guides you in terms of how you lead the company and what kind of people inspire you? For me personally, Warren Buffett stands out because of the model in which he leads the company. Maybe you can describe to us who inspires you day-to-day, and what kind of books you read.

[00:03:46] James: What, what I really liked about ICDCI then - today's Centum - was the fact that we were creating businesses. So, our business is to create other businesses and to make them better and to exit them. And in doing so, you're also touching lives. And we've had many examples of companies that we've been involved in, that we've scaled up where we've increased the number of people who are employed, improved livelihoods, and ultimately exited. And that for me is exciting. And the fact that you also creating new enterprises. It may be new enterprises or it may be scaling up existing enterprises. And I think to have a local platform that is a Kenyan platform where you're using Kenyan capital. Because many times when I've traveled to other parts of Africa, the biggest challenge is that the capital that is invested is normally foreign.

But here you have a company that has local shareholders. And it was established in 1967, specifically for that purpose. To mobilize capital from indigenous Kenyans, - in fact, that's how it was defined in the articles - and have their own vehicle that they could invest in. To have that sort of operation and to be a conduit of creation for me has been very inspirational. I've been blessed in my life to work with very exceptional people and role models many people read about, but have had a chance to work with. Whether it's my first boss, Tony Wainaina, who was exceptional, people like Peter Mwangi who later became CEO of NSE then Old Mutual. That’s somebody I worked with when he was an Investment Manager. When I joined TransCentury briefly, I worked with James Gachui and Zeph Mbugua very closely. Chris Kirubi, who we've worked with for many years, Donald Kaberuka, James Mugwe. So, I've had this wonderful blessing to have had a chance to have worked with truly exceptional people, and those people have been wonderful mentors for me.

I've been blessed in my life to work with very exceptional people and role models many people read about, but have had a chance to work with.

In terms of books, I read very widely. I know initially at the beginning of my career, I read a lot of finance books. Many people don't know that I taught accounting at Strathmore - ACCA Paper 3.3: Performance Management. I then introduced the CFA programme at Strathmore. I was actually the pioneer lecturer in the CFA programme at Strathmore way back in 2009. But then as you move from being an individual contributor to a leader and then to a leader of leaders, and you start focusing more on your people site and leadership development side, it's no longer technical. It's about how you influence people to perform, to perform better. And therefore the books you read tend to be a very eclectic mix. So right now I'm reading is Sun Tzu’s, The Art of War. I'm reading Sapiens. You don't understand people. Ultimately, you're getting results through people, and what motivates them. And that for me now is quite interesting. Earlier on, I spent a lot of time understanding strategy, organizational design…technical stuff. So, I have a wide interest; history, politics. In some industries, you are the largest player in the sector. You need to understand how economies function, how the political side interacts with the economic side. It's an evolution as you also grow.

[00:07:35] Mokaya: It's impressive that you also studied accounting. I have taught accounting. A lot of people also don't like accounting, so maybe you can inspire people to actually take some time to learn accounting. And people say it's also the language of business, don't you think so?

[00:07:52] James: When I was in secondary school, I did not think I would even study accounting. Strathmore’s Jim McFie came to our high school and they were interviewing students for scholarships to join Strathmore in January of 1996. I was one of those who were interviewed and the choice was between accounting and a program then called IDPM. I didn't know anything about accounting, so I picked IDPM, which was computers. Then McFie said, students come here and they don't really like computers, therefore you may want to choose accounting. And that's how I ticked the accounting and ended up at Strathmore.

And I loved it because the first semester we learnt Law, Financial Accounting I and Economics. Suddenly you can understand what is in the papers, you can read a set of accounts and make sense of it, and you have the basics of law; whether it's the law of contract, the law of tort, insurance law. And that's how I ended up studying two different accounting qualifications; CPA, and CIMA, and then later, CFA. It was a journey that was very accidental for me, but one that I really ended up loving and fell in love with.

What Makes a Great Business Leader

[00:09:09] Mokaya: I hope you can include such stories in a book in the future. We would love to read them and how you have developed yourself. One thing I would say also is sorry for the loss of a key mentor. But one of the questions I also wanted to ask was what key lessons have you learned from having interacted with all these people? What makes for a great business leader and business person for the people that you've interacted with and from the reflections from the books that you read?

[00:09:39] James: The interesting thing that I've picked up from these people is that they are very fearless. They are not constrained by what they have. When they dream, they don't dream starting with what resources they have. They dream focused on the opportunity and the resources are secondary. Say you're going to buy a company, and we've been in many instances where we went shopping for opportunities like when I started off even a Centum. The point is that you're making a bid for a company worth Kshs 2, 3 billion, and you don't have the money and you'll pick it along the way. They don't have a constraint mindset, which a lot of times we have.

The second thing is that they are problem solvers. They rarely focus on the problem. Many times it's a solution and how you can optimize whatever situation you're in. Too many times one gets stuck focusing on the problem here now, whereas time can be spent on the solution. The third thing is that they're extremely positive. Even when you're going through a lot of challenges or when the economy is very challenging, there's a strong sense of positivity.

I think the fourth one for me is they focus very strongly on their circle of influence and always work to increase their circle of influence. One thing Chris used to tell me is, James it's not enough to focus on your circle of influence, increase your circle of influence. If a policy is going to affect the business, it's your business to know and understand the policymakers, understand the environment, understand who's doing what, forge relationships so that you can influence. You want to minimize the points of surprise a process. So, relatively, very proactive.

It's about individuals who can create something from nothing. For example, when when I took over Centum in 2008, if you look at the balance sheet, we had Kshs 10m of cash and we had an overdraft of Kshs 170m and the limit was Kshs 200m. So it was like Kshs 40m. And when we started to discuss what was then now Centum 2.0, there was no limitation of where we would raise the money from and what would happen. And we didn't raise equity. Those are problems you, you know, you deal with. So, I think for me, that's the difference that I have picked from all the different people the great people. I've had the blessing to work with.

Centum’s Business

[00:12:24] Mokaya: I think at this point, it would be interesting to pivot to the business Centum and try to understand the business of Centum. A lot of people would want to compare it to Safaricom but Safaricom does tech and mobile tech in that regard. If they want to compare it with Equity Bank, Equity Bank is a bank. When you come to Centum, people get stumped a little bit. So what does Centum do?

[00:12:53] James: Centum is actually a simple business. We have capital, we deploy capital with the intention of creating and enhancing value in the companies that we invest in, and ultimately we realize that value through exits. We are not a conglomerate. We are not a holding company. We don't hold companies indefinitely. But we are in that cycle of creating more capital and creating value through deploying it and participating in the value creation. 80% of our time is in the value creation phase, where you have a portfolio and you're working on making those companies better and positioning them for an exit so that you can realize your value.

The only challenge with Centum is because you then have different companies in your portfolio at any given time. For an analyst trying to understand it as a conglomerate, it is difficult because the companies in the portfolio are dynamic. To put it simply, our investments are the inventory. If you compare us with EABL, you may have an inventory of Tusker, of various alcoholic products. For us, our inventories are the companies that are currently in the portfolio. And for everything in the portfolio, what we sell is not the products the companies sell. For the investment company, what is being prepared for sale are the companies themselves. For example, we created a company like Centum Real Estate. As Centum Investment Company, we are not in the business of selling houses. We're building a company which we're ultimately going to sell and realize value. That's a business we are in.

And if I take a step back, it has changed depending on how we funded it. In 2009 when I started off my tenure as CEO, this company had existed from 1967 to 2009, that is 42 years. And in that period, we had grown assets from certainly less than Kshs 1B to Kshs 6B shillings. And there was a feeling that this company could do more, but there were constraints. The constraints were the shareholders who were largely government and individual shareholders who were not keen to invest additional equity capital in the business. The model was how do we create capital so that… And they did not want to be diluted.

So, how do we deploy? The solution was, the only way you can then deploy is to: one, offload your non-performing assets. That's why, for example, one of the first actions I did was to sell RVR and a couple of other assets to build up some liquidity, but then invest in assets where you have scope for significant value growth with the intention of exiting. Because this is not an equity-funded model... If you look at most private equity investments, you go and get money from investors. They give you long-term equity, say 10-year money, and as the fund manager or the PE fund manager have 10 years to deploy it and return it back to the investors. In my position, it was a lot more challenging because then what we had to do was to go and borrow money. Take debt and deploy that to debt.

The challenge of deploying debt is that you then have both the principal repayment to make and interest repayments to make. So, you have a maturity mismatch between the investments you're making and the funding. But that mismatch arises because of the constraints that are there, which are, what funding model are they owners of the company comfortable with? In my case, the funding model they were comfortable with was a debt-funded model where the only concession they gave me as a CEO was then you could have a dividend freeze. The intention was to build assets, sell, pay down the debt, and then be left with capital of our own so that in the next cycle, you could then have a longer-term holding period. When you’ve funded an investment portfolio with debt and the debt is maturing, you have no option but to exit to repay the debt.

Centum is actually a simple business. We have capital, we deploy capital with the intention of creating and enhancing value in the companies that we invest in, and ultimately we realize that value through exits

The second thing is that dividend yield is going to be lower than the interest component of the debt because the average dividend yield of a portfolio is going to be like 3% and you have a funding cost of about 13%. You have a mismatch of about 10%. You have to be very aggressive in creating value. And that's why you've seen over the last 10 years, we invested and exited about 10 assets, created that Kshs 30B of value in the process. Or realized Kshs 34B, Kshs 3B of which is dividends. Many people ask, James why didn’t you hold? You can't hold if you’ve funded it with the debt. If you'd had funded it with equity, then you can hold it. The second thing is that the dividend is a very small component of the return. Out of the Kshs 34B we got back, only Kshs 3B was dividends. Kshs 30B was capital uplift that is realized through the exit.

Now, what were we doing? What we were doing was building capital of our own. And the intention was that from the exits, we would then retire the debt so that eventually in the next cycle, the capital you'd invest was neither borrowed capital nor new shareholder capital, but the company's own capital. And that's what we were doing in 2.0 and 3.0 coming into 4.0 now. That's why coming towards the end of 2018/2019, again, because you are in many companies, you have a feel of the economy. The space you're operating is in the growth space. For you to create value in an entity, you're not betting on multiple expansion, you're betting on earnings growth.

Like in the case of Almasi, the company that we consolidated and which I was chairman of for about five, six years, when we started, EBITDA Kshs 600m. How you create value is moving that EBITDA from Kshs 600m to Kshs 2B in as short a period as possible. When you get Kshs 2B, you then start feeling that there are headwinds and there is pushback. Now, if this EBITDA comes back to Kshs 1.5B, which is, which is a Kshs 500m decline, and say a strategic investor was going to buy you off at 10x, that's a Kshs 5B reduction in your valuation. We started feeling that the headwinds were there and that it made sense for us to make some exits with the intention of paying the debt and retaining the residual capital, so that then - to the example, you gave earlier of Warren Buffett, remember that's also an old company - you are then not investing borrowed capital. You are investing your own capital. So, the first step is, of course, to pay down the debt, build your yielding portfolio because then what you want to risk in the next cycle is not the principal. You now want to start risking the income that is coming from the portfolio, but the business remains the same. The business remains; you go in, you create value, you get some money back either through dividends or shareholder loan repayments, and ultimately, for every company, the intention is to sell it.

[00:20:36] Mokaya: That's a really brilliant explanation of the business model. I would say a couple of things that people may miss out on sometimes is you don’t build to hold, you’re not intending to create a conglomerate in the sense of just having the businesses there, you’re intending to buy the businesses, improve on them and then sell them, and then whatever you make in profit, then you invest it in the next cycle if I understand it very correctly. Right?

[00:21:03] James: Yes. Precisely.

[00:21:07] Mokaya: In that sense then, because you own quite a lot of companies, you have a very good feel of how the economy's doing. And then, during down cycles like currently, debt is not a good component to hold. And I know you're doing a lot of deleveraging. Is that what informs your kind of deleveraging of the balance sheet?

[00:21:28] James: Yeah, because you have to take a view on the outlook of the economy. You do several scenarios. What kind of economy are you going to have? For us, coming out of 2017 when you had two elections…And the advantage of being in many businesses is that you can feel what demand is looking like.

If you’ve borrowed at 13%, and you don't have earnings growth of 13%+, then you're going to be underwater very quickly because the value uplift will not keep up with the interest only. For us, we said, look, we think it's going to be a tough five years. It is time for us to consolidate. We are sitting on close to Kshs 19B of debt. If we have a significant slowdown in the economy…Remember, private equity assets are illiquid assets. So you need to sell in favorable economic conditions. If we hold onto the assets, what's going to happen is that we’re going to lose the value uplift. These companies may even cut to dividends because the dividend is the residual of distributions, so that's the first thing that boards cut. But then you have contractual obligations and a lot of the value you’ve created may be lost. So, we need to preserve value.

The point was, the sensible thing to do is to exit at this point and pay down the debt because the intention was not for us to be a debt-funded business, but we got into debt because of the constraints that we had in terms of the funding model we had originally. The intention is for us to have our own capital and the feeling of the investors, the major shareholders, in 2008 was that this is a Kenyan company. If we raise capital, we will be diluted and we would rather take a longer time and create our own capital. That's where we are going to pay down the debt and build your yield portfolio so that what you then now reinvest is not the principle. You can then reinvest your income. Which means that even if you take on risks that don't materialize, you've not lost the cashflow side of the business. What you've lost, or really takes longer, is the principal repayment, especially if you assume that you're going to go into more difficult times.

Of course, that was in 2018/2019. We even ended up in a worse scenario than we had anticipated now with COVID and whatever impact it has had because now COVID affected not just Kenya, but the rest of the world. In hindsight, it was an excellent decision. I know it doesn't seem very exciting to investors who are used to Centum announcing deals, but the idea was let’s consolidate.

So far, we've reduced debt from Kshs 19B to Kshs 3B. So, we've deployed about Kshs 16B in debt reduction and increased the marketable securities portfolio by about Kshs 5B. About Kshs 21B has just been deployed over the last two years in consolidating the balance sheet.

Opportunities and Future Growth

[00:24:42] Mokaya: Given such a model during such times as this, it's time for a little bit of hibernation in terms of the business, because it's a tough time. But then at the same time, you’re also strategically exploring opportunities around you to see what types of assets you can easily buy during such downturns at a discount. This is the time to go to the market with your fishing net, there are lots of fish, and then you can easily capture them. What kind of changes are you making right now so that you are able to capture these opportunities and prepare for the next phase of growth?

[00:25:23] James: Erick, you won't believe it. Between 2019 and this year, we've looked at more than 150 companies. Let's start with how we create value. How we create value is; is there room for us to enhance EBITDA or the key driver of value three times in like four or five years deploying minimal additional capital?

First, there must be that opportunity for improvement. You're not looking to buy perfect companies. If you will buy perfect companies, you won't get a good IRR. And that's probably the reason why some of the large PE funds don't have a good return. It’s because you're so risk-averse. The company is ticking all the boxes, so you're now at the level of organic growth. If you’re at the level of organic growth, then you will end up with a 2%, 3%, 4% IRR, nothing more.

So, we are looking for transformation opportunities, but where the transformation is within more management efficiencies as opposed to market because the one thing that is really hard to change within a three to five-year period is the market positioning of a company. The validation of the product or service the company sells in the market and the need for that product by the market, it’s essential that that exists. It's essential that the team exists because creating teams takes a long time. We tried in 3.0 or to create new businesses and the most frustrating thing is around people and the team, so, if it doesn't have a team, then it doesn't work. If the market opportunity is not there, it does not work. And then now there's an opportunity to scale it up. And obviously, one where you can at least create value of at least a billion or two for it to be worth your while.

Those are the kinds of opportunities we are looking at, and where you can also get control, because if you're not in control of the value creation process and in control of the exit process, then you’ll create value and not realize it. And that's another challenge of the PE model where you see a lot of challenges that when you take minority stakes, they're very hard to sell because then you are the mercy of the majority shareholder. Getting a fully priced exit becomes very difficult. A lot of our exits have been successful largely because we've been selling controlling stakes, and selling to strategics.

A lot of businesses over the last two years have gone into survival mode because of what has happened in the market, and so a lot of those conversations have stalled or been deferred or companies have gotten into a lot worse situations. That's why we’ve looked at 150 and not closed any. But I believe, shortly we will. It's important to be disciplined because if you get it wrong in the private equity space, getting out is difficult and it takes a long, long, long time.

That's one thing I would tell people who are joining the profession. Be very careful before you pull the trigger on what are illiquid positions because you can get stuck in there even when you're trying to get out. It's important to really take your time and do a thorough job before you go in.

Key Areas to Grow EBITDA

[00:28:53] Mokaya: If I hear you well, then liquidity management is a key component of your day-to-day. Making sure that the company has liquid assets because you're also dealing with a lot of illiquid assets that take a long while to sell off. And if there is a fire sale, you actually are on the losing end of that stick and you don't want that. But also something else you've mentioned is about making changes so that you're able to improve the EBITDA, which is, for those who are not in the know, earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. You want to make sure that that grows and mostly you’re trying to cut costs or grow revenues. So, from the businesses that you've invested in so far, what's are some of the key areas where you're able to grow your EBITDA margins?

[00:29:45] James: They are typically four or five. Let me start on the input side. On the input side, you have to really look at organizational health because without dealing with organizational health, even if you focus on the financial metrics, it will not happen. We typically do a cultural survey, a survey of the enablers of the business; what is the state in terms of the competencies of the team, the culture of the team, their engagement et cetera, and you need to fix those things. But then, you're fixing those things to achieve a certain result. One of the major drivers of value enhancement is revenue growth.

The second most critical one is efficiency improvements. If I take the example of Almasi, 75% of the value uplift on EBITDA came from efficiency improvements. And now you start looking at doing a study of why are we not efficient? I'll give you a practical example. Our gross profit when we started was about 20% whereas the rest of the industry was 30%. So you have a 10% opportunity to be better. Why were we not as efficient? One, we did not have manufacturing capacity, so we were buying a lot of products from other bottlers who were like a reseller. The solution then is to invest in your own manufacturing capacity. Two, we were leasing trucks. If you have your own trucks, then again, you become more efficient. Three, our manufacturing processes were an issue, with significant downtime. Now, this is a rigorous thing. You're just moving step by step by step. To circle back, that's where organizational health is important because these things have to be done by people. So, that's the other area. What can we do to improve margins?

The third area is, how can we do it with capital efficiency? Because, if you enhance value by Kshs 10B, but you spend Kshs 10B doing it, then you don't create any value. Opportunities for capital efficiency are critical. To go back to that example, what we then ended up doing is saying, okay, let's consolidate the three bottlers so that we invest in one line to serve all three bottling plants. Let's consolidate the territory so that you can do it in a capital-light manner and then the business can be cashflow generative.

The fourth critical thing is risk management of the business. We typically work backward from the due diligence checklist of the buyer. What kind of business does the buyer want to see? What is his current state? And what is the gap? When they do their DD, you'll find the buyer is not interested in finding a long list of issues, whether it's on tax, whether it's on accounting issues, whether it’s on operational issues. That's what we work through the committees to fix and then creating the governance. Creating the governance that can enable the business to survive without you is very important because if you don't do that, then no one will buy it from you. It is so embedded in you. Being able to create a healthy organization that is attractive to a multinational because once you cross the $50 million mark, you’re then talking of selling to international organizations if you're selling to a strategic. They tend to be very rigorous and very conscious about risk and about things that can come and embarrass them, so you have to fix that. But they are also checking if this business can operate without you. So you need a parenting model that is more supervisory where there's an independent board, there are committees that function. Many of the companies who've sold, the new shareholders have not changed any of the governance structures we've put in place.

Those are all the pillars you’re building to build a more efficient enterprise to make it attractive to a would-be buyer and for you to optimize your exit valuation. That thing takes time.

The challenge that does not show up in the semi-annual investor briefings that we do: one is looking at what was the profitability of the company this year forgetting actually that our business is not even the profitability. Our business is the growth in the profitability. Then, the valuation increases, then you can exit at that higher valuation. And that is hence the mismatch between what you're trying to do and how the market perceives us because the market is used to more operating companies because most investment companies tend to be private and the metrics are very different from one where you're looking at it… It's like watching a tree grow every six months; oh what happened these six months? It didn't quite grow as we had expected. So it's a different metric.

[00:34:48] Mokaya: I think at this juncture, I will let you breathe a little bit and maybe inform people that we'll be taking a few questions from the 45-minute mark of the conversation. So if you want your questions to be picked up, you can check our pinned tweet, write down the questions, and help us elaborate on what you want to ask. We'll be digging a little bit deeper into the balance sheet in a little while. We are also doing a little bit of a trend, so you can check and see some of the key points that have been raised.

We've had from his personal side and from the business itself. The business is simply just to buy and sell businesses. It's a holding company. They don't hold for the long term. They seek to buy, make changes, and then sell to strategic buyers and maybe sometimes IPO. And one of the questions I received along the way was why you don't do IPO's every so often, given that our securities exchange also needs those kinds of companies. In the second part of the conversation, we’ll have that. At this point, I wanted to ask The Trading Room, do you have any questions?

Amu Power Failures and Lessons Learnt

[00:36:06] Trading Room: Well, the main thing that I'd want probably James to touch on would be on, just personally from his personal experience, is there any business that Centum has done an acquisition in, or invested in that has gone sour and how has that been for the company? How did the company take that heat and how did they get through in passing that? And on to the overall comments that shareholders have constantly made with most shareholders really feeling that the company over the past few years, we know that the past financial year Cenum gave a dividend, which was very commendable. But do you think that shareholders, because most of the time we've seen shareholders complain on the thought that the company doesn't really care about them in terms of dividends, because you know, for most of the shareholders on the NSE, they would always want to have an overview. The dividend bit is always when they think that the company cares for them. And possibly, I know that Mwango Capital wanted to ask on this, what would be the future of Centrum? Where do you see Centum in the next three to four years? That's on a short brief, not the 10-year long life span for investors who want to invest because the Kenyan life space for most investors is always every four or five years. Whenever we have elections, then things definitely change.

[00:37:25] James: Those are good questions. So let me start with the first question. What have we invested in that has not worked? Let me give you one. One is Amu Power. Let's start with what information did we have at the time when we invested and what were we doing? Amu Power is the Lamu coal power project. This was not our project. It was a government initiative to do a public-private partnership where the government based on their analysis, wanted to have a baseload power plant of 1,000MW. There's baseload and peaking power. Baseload is the power that is always available.

For example, people ask me why, why didn't the government go for renewables like wind and solar? The issue there is that it's not baseload. The production varies. To be able to have more of the variable, you need a larger base. Think of base like the foundational power.

The government under Vision 2030 had that idea, went for a tender for this particular project. And actually, our consortium did not win. We were in a different consortium, but then we joined the winning consortium and our role was to develop the project, to take it to financial close, and then sell our equity at that stage. Why it made sense for the country at the time is that it was going to be the cheapest source of power. The risk we were taking was the upfront development risk. It made sense to the board and the IC at the time in the sense that you're supporting the government initiative to add to the power in the grid, you're doing so at the lowest cost possible, and you're participating in an area where local investors should participate, which is to derisk the project, take it to financial close and then exit. The upside was going to be fairly attractive.

What happened along the way, and some of the risks that we did not quite anticipate were; one, there were a number of environmental issues that came up and that significantly delayed the period it was taking to get to financial close. In hindsight, we probably could have done more due diligence. But also, sentiment towards coal changed after a short period of time. It moved from one extreme to another.

The second thing that happened is that the power demand did not keep up with what was projected and the state of KPLC’s balance sheet deteriorated. Ultimately, a decision was taken to mothball the project using the tribunal. The lesson for us there has been one has to be quite careful on value creation that is dependent on external actors because you're not really in total control of the process. You may think you are, but you're not treating control. I think for us, that has been the lesson. And what we then did is, we impaired it in full. We had spent about Kshs 2B shillings and we impaired it in full. So that's one of the projects that we did and where there have been lessons learnt.

Dividend Payments and the Future Outlook

On dividends, over the last six years, we've paid Kshs 4.1B in dividend. We’ve been paying Kshs 1.20 and this year we reduced it to Kshs 0.33. I'll come to that. In aggregate, over the last six years, we've returned Kshs 4.1B to investors. I just want us to look at it, say, over a 12-year cycle from 2009, because I can take responsibility for what has happened since 2009. I started off with exactly Kshs 40m in cash. We've not gotten any capital infusion from any shareholder. I’m one of the CEO's who's been on the NSE who’s never raised any capital from any shareholder. All the capital we’ve raised to invest has been debt capital. In that period, you then have to both invest, exit, pay interest, pay principal, and still return capital to shareholders while at the same time building up the liquidity buffer of the company. So, there's a trade off, no matter how exceptional you are, it's hard to achieve all those things. If the capital we had initially was equity capital, then all the capital we've spent in interest and principal repayments of debt would have flown to our shareholders.

Unfortunately, it was not because a choice was made not to raise equity capital, which would then have had the resultant effect of diluting the existing shareholders. The existing shareholders, younger shareholders, preferred not to be diluted but to build capital in the company using borrowed capital. So, we've returned a significant amount of capital back to providers of debt capital and we raised two bonds in the market which we've paid, we had bank debt which we've paid and we've paid interest. At the same time, the shareholders wanted us to build our own capital base, so that then, to the point Erick was making, we don't invest borrowed money but rather you have recurrent income, like say what Berkshire Hathaway has from his marketable securities portfolio, so that is what you're investing. So, at the same time, you're building that. Now it's about Kshs 8B. At the same time, you then have distributions to make to shareholders. So, it's a balancing act. Over the last six years, we've done over Kshs 4.1B.

The target now we have is to pay 30% of annuity income. Why annuity income? It’s because we are no longer reliant on exits. We now have enough capital of our own that is generating annuity income for you to sustain a dividend stream from the annuity income. What happened in 2020 was really unprecedented because, with COVID and what happened to the economy, a majority of companies cut their dividend and you know it was unprecedented. Even as you're coming up with a dividend policy, you don't anticipate, even in your wildest risk scenarios, that this would happen. So, the first thing, and you noticed on the NSE, and action companies took was to cut the dividend. If you're sitting as an investor whose primary source of income is a dividend, then that has been cut.

Then, remember now the exit environment is not attractive, so, you again can’t exit. Fortunately for us, we had built up this annuity income stream, which is why we still paid a dividend albeit reduced. But we just had an abundance of caution where our directors felt their primary responsibility was to the company. And because you’re also going into elections, and you're going into another cycle, you don't know what's going to happen, we perhaps need to be a lot more cautious, but nevertheless pay dividends to shareholders, which is why we reduced it.

What's the future outlook of this business? It's important to understand what we've been trying to do. We've been trying to build capital out of almost nothing. You've borrowed and you've taken advantage of the environment as it was to create capital, you've paid back and now you've built your own capital. My own target and the target strategies, in three years’ time, we should be able to generate an annuity income of Kshs 3B to 4B every year.

With that kind of money, you then can afford to pay a dividend of 30% of that, so Kshs 2. That's Kshs 1.2B. You have a fixed cost structure of about Kshs 400m and the rest is available for investment. You can be investing about Kshs 2B to 3B every year without needing to borrow. It's going to be one of the few local institutions that are going to be capital surplus and generating capital on an annual basis that is available for reinvestment. And that's what we've been working on. It's been a journey that has taken a while. We've been 12 years at it. In that period we've had a lot of challenges, but that's really where we are going.

Share Price and Share Buybacks

[00:46:31] Mokaya: A quick question then, given that you raise a lot of debt. Some of the complaints that you get from shareholders, of course, is that the share price has been sinking for a while. Do you feel like it may be profitable for investors to actually be more invested in your debt than in your equity so far because the returns seem to be flowing to debt-holders so far? I know you're keen on reducing the debt overhang so that you're able to have a lighter balance sheet in terms of debt, but then going forward, how could you comfort shareholders who've been burnt in the process of holding the share? Something else you've talked about is share buybacks. Maybe you can give us a little bit of a brief on how you're thinking about capital returns to shareholders going for dividends and share buybacks.

[00:47:27] James: Let's start with the debt and then the share price. On the debt side, we've already paid all the long-term debt. We don't have any more debt, so there's no opportunity to invest in the debt of Centum. Some of our portfolio companies have issued debt. That may be an opportunity. But remember, this debt is earning 13%.

On the share, it really depends at what point you came in on this journey. What I've noticed with our share price is that it's highly correlated with the index. There’s a time when the index really rallied and the share price sort of moved in tandem with the index and in a sense, even at a premium to NAV. Then, the index has been tanking. At the time when the index had rallied, it was really driven by local investors. Now, if you look at the history of Centum, up until 2007, our articles did not even allow foreigners to invest in Centum. Actually, ownership of Centum was restricted by law because Centum was established through an edict of the president, President Jomo Kenyatta, in 1967 as a subsidiary of ICDC. It was established to be owned only by Africans.

The problem with that is that the rally happened driven by local investor participation, the share holder profile of Centum remains still local - we have less than maybe 2% or 3% foreign shareholding - but the stock market today is driven largely by foreign investors. Then, you have a very limited free float largely because the main investors don't sell. They keep on buying. There are also a lot of shareholders with small holdings who have bought and kept for a long period of time. One of the challenges we've had is the free flow not being there for institutional investors, and therefore as the rally has happened.. we are not like a Safaricom where you have a very significant institutional and foreign shareholder participation all the way from the get-go when they did their IPO. That has meant that as the index has come down, the price has been correlated with the index and it has gotten disconnected to NAV. And so, the issue has been around the share buybacks because what share buybacks do is reduce the overhang and they reward everybody. If you're distributing, say Kshs 1B, you are now distributing to fewer shareholders.

The only challenge in the real-life is that you have multiple priorities. You have an economic environment which appears very uncertain. If it was certain, then one would have said, let us deprioritize deleveraging and focus on applying that capital to share buybacks. But because the environment is uncertain and you have competing needs, then the competing needs for the capital have been let's first deleverage, let's prioritize the deleveraging and also prioritize building up the recurrent income portfolio, then we can use this recurrent income. Instead of distributing it entirely as dividends, some of it can go towards the share buybacks. As a CEO, you end up solving now for the long-term shareholders and I've been fortunate in the sense that the shareholders who are represented on the board, ICDC and Chris, have been longterm. You cannot solve for everybody now. There's somebody who’s just come into the boat in 2016, there’s somebody who came this year...You have to get the class you're solving for. And because the long-term shareholders have a long-term view and understanding of where the company is going, then they can exercise patience to say, okay, let's first do this thing so that then, when we start doing a buyback program, we can sustain it from recurrent income as opposed to from exits. And so at this year’s AGM, we’ll be amending the articles to allow for the buyback so that is one form of returning surplus capital back to the shareholders. Hopefully, that will reduce the overhang.

Evaluating the Company’s Financial Statements

[00:52:03] Mokaya: I think I can hear a lot of ululations from the shareholders who have been pained for a while. I think share buybacks have been a boom at least for NMG. I think it's boosted the share price short-term, giving it winds in the sails. So, I would say that's a brilliant initiative.

A couple of questions which are being raised, and I think it would be nice if you could deal with that, the bare case for Centum. One is, the books are complicated, and are you cooking the books? That’s a question that has come up. I think in that regard, a question I had in mind myself was when I was in school here, one of the CEOs of a company like yours in Sweden came and they IPO’d and one of the biggest challenges was of course explaining the business and the business model to investors and to analysts to help them understand all this. And one of the challenges is that you're kind of a holding company. The businesses under you, you don't fully own them. You partly own some of them, so it's really difficult to really explain what you do and at the same time to explain your books to investors. Take us a little bit through your books and help us understand the key movers and key places investors should be paying attention to as the business you lead.

[00:53:35] James: In our set of accounts, there are two sets of accounts. One is the consolidated financial statements. The second one is the company’s financial statements. The consolidated financial statements are a Companies Act requirement for companies that have subsidiaries. However, I'll come to this. There's an exemption for investment companies. I'll come to that point.

Let me take a well-known conglomerate like East African Breweries. East African Breweries under it may have Kenya Breweries and a couple of other subsidiaries, but these subsidiaries collectively are integral to the operations of East African Breweries. For you to have a sense of how East African Breweries is doing, you will then take Kenya Breweries and before then, Central Glass, and a couple of others. These are put together. Or KCB. Or Equity Holdings. They have banks. These are homogeneous businesses and these entities in aggregate tell you about the performance of the business. So the framers of IFRS and the Companies Act, the intention is for you now at the holding company to have a set of consolidated financial statements that give you a view of how these entities, which operate together as one homogeneous entity, are performing Those are the consolidated financial statements.

When you apply that consolation principle to an investment company, it doesn't make sense because these companies are not homogeneous. These are disparate groups of entities. Some of them they're wholly-owned, some of them are subsidiaries but maybe are 51% owned, some are 30% owned, and are in very varying industries. When you consolidate them, frankly, what you end up with doesn't make a lot of sense to anybody and has contributed to the confusion that investors have. When you report on consolidated accounts of the companies they are used to, whether it's KCB, Equity, Safaricom, the focus is on the consolidated. Now there's confusion because then when you come to the investment company, the company accounts are the ones that tell you how we are doing as an investment company. How much dividend we've received. For example, in our consolidated entity, you cannot tell what dividend we received because it's netted off in the consolidation. The company P&L is what tells you how the entity is doing, but the emphasis then tends to be on the consolidated. I have even seen analyst reports where they're analyzing the balance sheet of the consolidated entity where you've consolidated a bank with a real estate company, which are totally unrelated, in one entity.

There's a window in the Company's Act that gives the investment companies exemption from preparing consolidated financial statements if the intention is to hold the companies for purposes of sale, and that's a conversation we are having with the auditors and our audit committee to see whether that's a window we want to take. That's something we're exploring because now there's a lot of confusion and in that confusion, value is destroyed for everybody. The set of numbers that tell you how we are doing as an investment company is the company P&L because what you see at the bottom, the total return statement is telling you what dividend we've had, what expenses we've incurred, and what revaluations have been done. And if you look at the last two years, the previous year -10%, this year was -8%, which is consistent because we've had a lot of revaluation losses. The company balance sheet just takes the assets we hold in terms of evaluation of the instruments we're holding, whether it's the equity instruments, less the debt, and you arrive at the NAV. That gives you a sense of how the company is doing as an investment company.

Accounting Practices

[00:58:01] Mokaya: In that regard, a question that came through is, also have you been a bit aggressive in the fair value gains aspect of it?

[00:58:13] James: So if you look at our company P&L for the last two years, we've had impairments and revaluation losses of 10 billion. So we've been fairly conservative in terms of the impairments we've passed and the evaluation losses that we've passed. For example, a company like Amu Power, we wrote it to zero. So if you look again at our exits with the exception of one company called King Beverage, which we sold below cost, all other companies we've exited at a premium to carrying value, all other exits that we have done. I think the evidence suggests otherwise.The NAV has come down of Centum over the last two years by 10 billion, largely on account of revaluation losses, which we've passed through the company P&L.What creates confusion now in the company is a requirement to revalue investment property on an annual basis. So you have a lot of wild movements there. So either up or down. And so that's why whenever I do an investor presentation, I emphasize just focusing on the company P&L, because even the dividends will be paid from the company’s P&L. I'll give you an example. A lot of business journalists ask me, and even one of the main journals in this country ran an article that said, despite Centum booking a loss, they paid the dividend. You see the loss was in the consolidated P&L. If you go to the company P&L, if you exclude the evaluation losses that went through the P&L it was actually profitable.

The entity that is paying the dividend is not the consolidated entity. It is the company itself that is paying the dividend and the revenue reserve is the revenue reserve of the company itself, the entity itself. So you can see the confusion it creates even for respected business journalists, but that's largely because I think to your point, Eric, when you began is that, Centum is the only company of its kind and the other companies that are similar are running homogeneous … They're not investment companies, they're running, operating businesses where the subsidiaries within them are part and parcel of the operations of that company. So that's the distinction.

[01:00:49] Mokaya: So perhaps then a key aspect of maybe the balance sheet then is maybe a question I would ask, what does a perfect balance sheet look like for you? And then in accounting for the various businesses since you have various amounts of shareholding and some of them like CDM own through another subsidiary on CDM and then directly own through CDM, we won't see them itself. So how do you do the accounting for all these businesses and especially in the consolidated business itself on the consolidated level, how do you do that?

[01:01:23] James: So the consolidated level if you're looking at the consolidated accounts, we then aggregate the P&Ls of all those companies that we hold more than 51%, as if we hold a hundred percent. Then you deduct the minority interest through what is called minority interest at the bottom. Now, what is reported is the aggregate as if it's a hundred percent, because the minority interest is done as a disclosure at the bottom. At the company level, for CDM, the only thing that will go into the P&L is if there's been a dividend, that is going to go to the P&L. If there's no dividend, then it has no P&L impact. If we have an impairment, i.e the value now is below the cost that passes through the P&L. If there's a downward revaluation that goes through other income, OCI, what is called OCI just below the profit after tax. So that's how we account for it.

[01:02:32] Mokaya: Okay. We may have lost a few and in that . So I think then I've been skeptical of using just the company itself, being concentrated a lot on the group level. So that helps a little bit explain that. But then in terms of a perfect balance sheet, how does that look for you going forward?

[01:02:55] James: What are you trying to achieve? Let's go back to where we began, where we began, the company has been there for 40 years. When I took over in 2009, the last share issue we had was in 2009, and we only raised 300 million shillings. We need to scale up, otherwise you're going to be totally irrelevant. If we did not do that, I would not be on this call today. Centum would have disappeared, like another irrelevant entity. We need to scale up. So we need to scale up using debt and you need to invest in assets that will give you growth. So you cannot borrow and put your money in bonds.

You must borrow to get assets that will give you growth and an exit. You must exit, you can't hold them because if you hold them, what will happen is that the debt will overrun you and build capital. That's where we've been. The phase we are in, is we want to invest income. So you now need a segment of the portfolio to be a recurrent cash income, generating a portion of the business. The rest of the balance sheet you want it to be a high growth business. You want it to be assets with potential for value uplift. On the debt side from our perspective, actually I think we have achieved that objective because the objective was to retire all long-term debt. You're just left with the lines of credit that we have, which you typically use for bridging finance purposes.

So we have a line, it's approximately 4 billion shillings. So it may be up or down depending. So that if you have any need for liquidity, you draw down on that line. So that's sort of how our balance sheet,... it's a simple balance sheet. That's how it should look like. So either the assets are there to give us growth or the asset is there to give us recurrent cash because the group side, the cash is very lumpy. So you cannot rely on that for recurrent requirements, particularly a dividend.

The High Yield Portfolio

[01:04:53] Mokaya: A statistic I have here is 93% of your high yield portfolio is in cash and fixed income. Is that something that is deliberate in terms of keeping liquidity?

Source:

[01:05:03] James: It is something that is deliberate from a management perspective. Because you see on the growth side, you're already taking a lot of risk on the value. So a lot of these assets we've invested in the high yield portfolio are the returns we made from the exits we did in 2017 and 2018. Now the biggest tragedy would have been to put those assets into shares because now today we would have lost like 30% of value. So the purpose of that portfolio is to generate a yield. So right now it's generating about 14, 15%. That's the objective of that. Then now you have the risk assets, so in those you can have fluctuations in value. You may have a depressed year but because you are now not investing debt, you're sort of just investing your cash. You can be able to absorb that risk on the non high yield assets.

[01:05:57] Mokaya: So if the yield of the portfolio is 14%, are you saying or implying then that your expectations also to move this money from this high yield portfolio to an actual investment, you have to earn a return of at least 14% to be attractive?

[01:06:16] James: No, no, no. What you want is the risk return. The return is a function of the risk you're prepared to take. So if you're earning 14% on your yield portfolio, it means on a billion,... say today we have seven and a half billion. So on seven and a half billion, you're making say 1.2 billion.

Okay. Now, if you invest the 1.2 billion, you want to invest it at 25% IRR, upwards of a 25% IRR, because that investment you're making in the PE has a higher risk. It is illiquid. It is not generating for your current yield. Things may not work out as you had anticipated. It may take a lot longer. So each asset class has a different return expectation based on the risk you're looking to take. It's not homogenous.

[01:07:11] Mokaya: Okay.

[01:07:17] James: In aggregate you will probably end up at around 20%.

Exits

[01:07:21] Mokaya: So another question in terms of exits, we haven't seen a lot of IPOs given our securities exchanges need companies that are exiting.

[01:07:34] James: Do you know of all the investment companies, at least we are one of the few that has brought some of our companies to the market? People forget that we brought Longhorn to the market. It was a private company, so we brought it to the market. Our markets are not ideal for exits. And I'm saying that having served on the board of NSE. The reason is that if we had attempted to exit our Almasi on the market, one, we wouldn't have gotten a 10 and a half times multiple.

[01:08:04] Mokaya: Yeah.

[01:08:05] James: Two, the highest price exit for some of these companies is to a strategic investor, not to the public. Now a strategic investor will pay a premium because they have synergies with the existing business, the public, not necessarily. So then we also have handicaps. When you come to sell, you cannot sell everything because then the company will be left with no owner. Remember, here you are the majority shareholder. So the company has to transition to another owner. So it cannot come and be sold, and now it is ownerless. So the highest price exit for us is to a strategic investor. That strategic investor, many times for them to undertake the synergies that they want, many times they want to remain private.

The highest price exit for some of these companies is to a strategic investor, not to the public. Now a strategic investor will pay a premium because they have synergies with the existing business, the public, not necessarily. So then we also have handicaps.

And from our perspective, we don't have lock-ins. We don't, it's a short term period. You have a bigger universe of investors to choose from. And sometimes you can even get a better price. That's why our model is not necessarily consistent with exiting through the market. Because if you exit 53% of Almasi to the market, then who's left owning the company. Who's left steering the business and we've been preparing it to be acquired by somebody else as strategic then sort of bolt it onto the existing company, to get further synergies. That's the only way you can justify a multiple of 10 and a half. If it was a financial investor, maybe you would get at best seven. That's the challenge of exiting control stakes. Maybe you can exit minority stakes onto the market, but minority stakes are not attractive to us because if you get a 10 times EBITDA you'll get a significantly lower sort of multiple.

[01:09:55] Mokaya: Yeah, I should say also I've seen a lot of questions on Centum Re and Two Rivers and I would say that at some point in the near future, we may host Centumre. Those questions would be best handled there given the limitation of time. So I would say then you can keep the questions until then. But if you have any comments yourself on Centum Re and Two Rivers, maybe James.

Centum’s Business Model

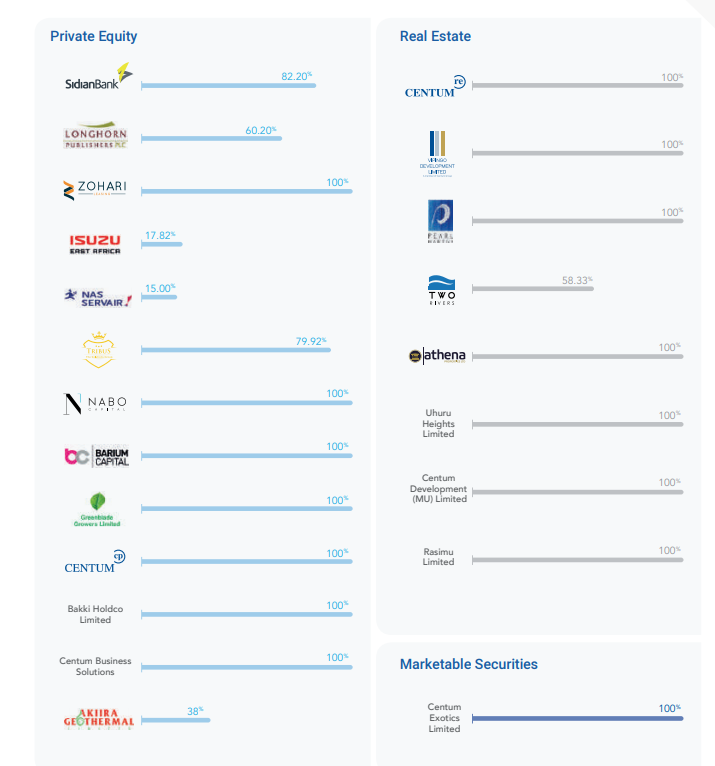

Source: Centum

[01:10:27] James: What our business model is, is to create entities, create value and exit. So Centum Re our business, our CACP is not to sell houses. Our business is to make Centum Real as valuable as possible so that we can exit. Someone running those businesses is now selling the houses. One, the CEO running the operating business. So Centum Re, we invested seven and a half billion or 7 billion. We've gotten back about four and a half billion. So we have two and a half billion invested and we're probably going to recoup our entire investment in the next one or two years. What is going to be left there is profit.

Source: CentumSo the question then, how do you realize your value? TRDL is the same, it's something we created a company from scratch. We invested about 1.9 billion. We've gotten a lot of it back. We still hold 58%. A lot of it is sort of our profit. And that's our business model because we ended up raising the entire deal about 20 billion, but you're sort of raising it at value uplifts and significantly by higher value uplifts. And that's why the dilutive impact was not big on us. We still have 58% of that business, but relatively speaking, we are the investor that was putting in the least money. And that's really our business model is to come in early and create value. So that even if there's a risk, then you are risking less. But also remember we had no choice. It's not like we had a lot of money to invest. So it was that you're taking a high upfront risk, scaling up, attracting capital at higher valuations and ultimately exiting your position. So we are not necessarily embedded in real estate as an asset class. It's just that way back in 2009, 2010, when we're looking at which asset class had the potential to give us that 30% IRR, real estate was it. And if you look at Centum Re, as an example, because Centum Re excludes TRDL, we are there. The thinking was not wrong.

Source:

There were some asset classes which got to do very well, like power, where we've actually deployed more capital than we've deployed in real estate, which did not perform as we had expected. So it was a view we took. We are enterprise builders. So, Centum Re, I'm proud that we moved from bare land to an entity now that has a board, that has a credit rating. And part of the reason we wanted to issue the bond is that we wanted to have a market instrument. So you're moving to an investment credit entity.

That's really our business model is to come in early and create value.

If an international development company is looking at East Africa and saying which entity can I come in as a platform company and acquire if I don't wish to start from scratch with the governance, with the systems, with the processes, with the sales teams and the rest, then our Centum Re is there, up there and you can due diligence it, fully compliant from a tax perspective, et cetera. And we are not emotional about owning assets. There's no emotions with it for us. This is the business vein. We create and everyone who works, even in those companies knows that the purpose of their existence is to create as much value in the entity as possible so that they can be sold to a different owner.

Synergies Between The Portfolio Companies

[01:13:55] Mokaya: So in terms of these businesses that you own, one question I was thinking about the disparities, are there synergies, say between Centum Re and Sidian do you like require your portfolio maybe to bank with Sidian so that then you kind of leverage the books so that the money is flowing within these business models you've created. So do you see a lot of synergies between the portfolio companies that you own?

[01:14:24] James : We encourage, we don't require because if you require, it's very easy for you to fall into now value destruction. So in fact, our parenting model is supervisory. We don't want to be the ones doing operations of businesses. Our role is to build entities at work that kind of function on their own. So you'll find Centum Re for example, the other day I think they have signed a partnership agreement with ABSA.

They're fine, same with other banks, because I want to be able to hold those CEOs accountable for the deliverables, without them saying, look you tied my hands by requiring that I work with entity ABCD. So we encourage as much as possible. And that's to the extent that it makes sense to your business, but we don't require it, because from experience, what we found out is that it's very easy to get into value destruction.

Capital Allocation

[01:15:23] Mokaya: All right. I think I want to ask maybe a question on capital allocation. It's a question maybe I failed to ask at the beginning. If you look at Centum itself you have this allocation to private equity or real estate. How is that looking like presently, in terms of capital allocation and then going forward, where would you want to be?

Because there's also a bit of worry among investors that the exposure to real estate is a bit too high and some of the issues some companies are having in that space. Then there's a little bit of worry there. So do you then want to maybe assure investors that at some point you maybe shift towards more of a PE based model, which most people may be interested in, Centum with that thinking in mind. So capital allocation, how you think.

[01:16:16] James: So let's start at the asset class level, then we come to the assets level. So from an asset class perspective, I think for us now it's a misnomer even to speak of real estate because Centum Re is an operating entity like any other entity. So actually now you can consider all of them to be private equity assets. It's just that some have been more successful than others. And the idea is to quickly move them along the maturity profile and exit and re-allocate now based on not so much asset class based so much on the three things I'll talk about. One, we look at what is the IRR potential of the money you've invested. Does the IRR exceed your threshold?

Two, what is the NPV relative to the risk? Because you don't want to do a lot of work for an NPV of 200 million. You want it to be a billion and above relative to the risk. Three, how does that asset sit from a risk perspective in the context of the rest of the assets in the portfolio? Is it in the same industry? Is it exposed to the same factors? Is it helping you on diversification, et cetera? So that's the thinking in terms of new assets. The idea is to deploy the income coming from our yield portfolio. So the idea is when you do exit, you say, call it into the yield portfolio and income, and that income you then deploy using the criteria that I have mentioned to you.

In real estate, it's not that we invested a lot of money. It's that we are relatively successful in that asset class, just as we were at one point in beverages. It's not that we had invested a lot of money, we're successful. There are places actually, asset classes where we've invested more money, but we've not been as successful. So all the assets we have are sort of on a journey, the value creation journey, the ultimate success is a profitable exit. That's what you consider success for us as an asset manager. And ultimately, and ideally what my own ambition is for this company is for you to be able to have its own capital. So you don't have to go and look for capital and get it on video, never stamps. As we deploy capital into new assets using sort of, from a return perspective, the IRR NPV relative to risk and thirdly where it sits on the portfolio.

[01:18:56] Mokaya: A lot to digest, but I think one of the things that would maybe give us an example as it relates to your real estate portfolio. I follow Warren Buffett a lot. I think in 2016 he invested in Apple and now it's around 40% of their portfolio. They did not go about intending to own 40% of their portfolio to be in Apple. As your investment grows, kind of sometimes just find yourself that the portfolio, the cost that you wanted in terms of capital allocation. So I think then in that regard I would ask you what would be your ideal portfolio allocation towards these various asset classes?

Regional Expansion

Another question I have received is about regional expansion. Maybe investing beyond borders, how is Uganda doing? And are you also thinking about deploying capital in other parts of Africa? And maybe finally a question on have you considered maybe doing a venture capital arm at some point, and maybe investing in like small businesses so that you can maybe also be tapping into say the companies like the Nigerian companies that are growing very fast, like Flutterwave? So have you considered maybe forming a venture arm of Centum?

[01:20:18] James: I think I’ve answered the asset class question. Let me just answer the question on regional expansion. What you've decided to do is to support our portfolio companies to expand in the region because we are fortunate to be in Kenya. Because Kenya has the most developed financial markets in the region. And actually we think about Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Kenya. These are the niche capitals. Kenya is very attractive for investors. And that is important when you come to selling. Investors are very comfortable with Kenya. So Kenya is a good base and many companies as they scale up they need to sort of expand in the region. And we've supported a lot of our businesses. A company like Longhorn is now all the way in West Africa, in all these African countries and many companies who we supported from that particular sort of perspective.

Kenya is very attractive for investors. And that is important when you come to selling. Investors are very comfortable with Kenya. So Kenya is a good base and many companies as they scale up they need to sort of expand in the region.

But I think being in Kenya is a significant competitive strength for a lot of companies. Because when you go to engage with even strategics, no one asks you about macro economics or politics. Most people who are serious about Africa, understand Kenya, understand Nairobi. So I think it's something we are lucky to have. Regarding VC, a few years ago we did sort of some small ticket investments in greenfields and startups, but we were not very successful for a variety of reasons. One was even where there was market validation, scaling up was a challenge. So it's probably, we didn't do it well, it's not something we did well, based on the results we got. And so it's not something we are currently focused on doing, because strategy, Eric, you need to focus. There are many things you have to say, you're not going to do for now. And so there are many things we have said, ... they are nice to do. They're very good. But it's about choices and that for now we are not doing. We did not have success, so we don't have validated learning or evidence that we did it well. So at the moment, it's not one of the priority areas for us.

Reflections, Lessons And The Vision

[01:22:36] Mokaya: Five minutes to the top of the minutes that you had allocated to us, so I wanted to ask maybe any reflections on past mistakes and maybe lessons that you're taking with you as you go forward, maybe useful as you build Centum for the future. So you can also share your kind of vision. I know you've shared a little bit in bits and pieces, but what would you envisage Centum looking like as you head towards maybe elections next year, as you also navigate the boat past that 2025?

[01:23:09] James: I think for me, Centum is a truly Kenyan company. It's a company I've had the blessing of leading for 12 years and been part of for 20 years. So I'm playing my part in it. And really my dream and aspiration is that it will be like the UK equivalent of a CDC, where you have your own indigenous company. CDC is funded by the government. We are not funded. We have to be entrepreneurial, that is able to be a source of equity capital, because in this market, you have a lot of debt providers. You have equity providers but they are foreign. Even the funds are, the PE funds and other funds, majority of the capital that they invest is foreign. But having, I think a local company that is well run, well governed that generates capital, that deploys capital, I think that's for me is my ambition, sort of my aspiration for this entity. And having moved it from a level where we were relying on debt to a level where we now have our own money to invest and where we can really improve enterprises. I think if we achieve that for me, I'll consider it a success. And it's a genuine ups and downs with sometimes the setbacks, but that's really the journey we are on. And in the process, we need to solve a lot of the other issues, especially sort of share price issues, et cetera. But for me it is just to remain true to that north star and and just keep my eye on the ball in terms of taking the company there.

And really my dream and aspiration is that it will be like the UK equivalent of a CDC, where you have your own indigenous company….having a local company that is well run, well governed that generates capital, that deploys capital, I think that's for me is my ambition

Kindest Thing and Closing Remarks

[01:24:58] Mokaya: All right. So maybe a final question also would be then what's the kindest thing anyone has done to you in your professional career?

[01:25:08] James: I think the kindest thing anyone has done to me is giving me an opportunity. The board of Centum was very kind to give me the opportunity to lead this company when I was only 30years and they could have picked many people, but they thought I could do it. And to take that risk on somebody like me, I think, is extremely kind and gives one a platform, sort of an outlet for their creative talent. A lot of people have great ability, but they don't get opportunities. And that's something I've tried very much to pay back by sort of the various programs we've created, whether it's a graduate program, sometimes when recruiting more than we need, just to give people the same opportunity that was given to me.

And to take that risk on somebody like me, I think, is extremely kind and gives one a platform, sort of an outlet for their creative talent. A lot of people have great ability, but they don't get opportunities.

[01:25:53] Mokaya: Great. Any closing words?

[01:25:59] James: I want to thank all of you for your interest. I can see the huge numbers on this platform. It's a real pleasure to be on the platform to say I'm always very much available. I appreciate all positive, negative feedback. That's part of the growth journey. And just urge everybody, let's just be proud of our enterprises. Let's encourage them. Let's correct them where they're not doing well.

And to say for me, despite what we consider challenges in this country, I'm still very bullish about our prospects and remain very confident and sort of optimistic about where we want to end up as a nation and as a people. So I just want to thank all of you for participating, for taking time to listen to me and you, Eric for the wonderful and insightful questions. And for the way you've guided this particular session, it's the very first of such sessions. And for me, it's been a learning opportunity as well. Thank you very much.

[01:26:53] Mokaya: Thank you for joining us. I hope this is your first of many. You're welcome every time you make the announcements on results to always come by and explain to us. I think the aim of such platforms is basically to just create a place where people can talk to the management teams around, and learn from them. I've seen a lot of these in other places. So I think it's something that you can adopt, and we can demystify the companies that we have around, able to understand their business models, how they make money and how they do their thinking and what their relationships are with each other.

So I think that's the whole goal on a platform like this, and it's really nice that you took one and a half hours of your time. I know it's a very busy time, as you prepare for the AGM. So you're very appreciative of that. I also want to thank an entire team that I work with in the background who I work with to come up with questions. We've got a huge document, a couple of questions and briefs. So we have Bonnie, Eric, Becky, and Soud in the background making sure that everything is going well. So I'm very appreciative of that.

Also the team Centum that helped us get in touch. Thank you so much, we appreciate it's been a long week in terms of back and forth engagements. So I think it's also really nice that we have you here. So looking forward to also hosting your portfolio companies, send them here so that they can explain what they do and you can hold them accountable. Hopefully soon. Thank you for tonight and see you next week.